Nothing but praise also from the (inter)national press. People are impressed with the ‘new’ architecture and the ‘new’ interior, and of course the unique collection of paintings and applied arts. In the British Financial Times, Simon Schama rejoices in the reunion with his ‘long lost friends’ – the paintings of Metsu, Vermeer, Ruysdael, Van Bruggen and of course, Rembrandt. The New York Times headlined: ‘The Rijksmuseum, Reborn.’ In the national press, the reopening of the museum is celebrated mainly in quantitative terms: 8000 paintings in 80 galleries, 2500 visitors per hour, more than 75.000 tickets pre-sold, open again after 10 years of renovation with a total budget of € 375 million.

For Amsterdam, the reopening of the Rijksmuseum is fantastic news. A little more patience will have to be mustered for the Van Gogh, but soon the quartet on the Museumplein – old, new, iconic and classical – will be whole again. Throw long visitor queues into the mix, and the perfect picture of a flourishing and (commercially) prosperous cultural sector is complete. A picture the city can flaunt to compete with other cosmopolitan cities such as Paris, London and New York.

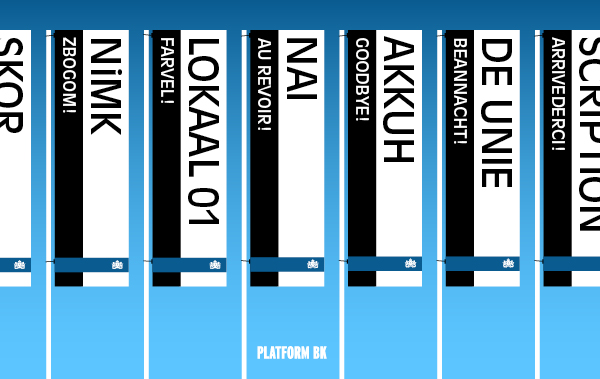

However, as we know by now, nothing is what it seems. While the Rijksmuseum opens its doors, the recent art cuts have forced other arts institutions in Amsterdam, such as SKOR, NIMK, Virtueel Platform and the Tropentheater to close theirs. The cuts did not only impact Amsterdam’s artistic landscape; in Breda Lokaal01, and in Almere De Paviljoens are closing as well. And that’s just the tip of the iceberg. In the coming years, this scenario looms ahead for other institutions, and if they manage to prevent closure, they’ll have to curb the blows by firing staff, reducing programmes and acquisition budgets or seeking to merge with other organisations. A fate, which has struck some of the organisations behind the restored facades on the Museumplein as well. And here I am not even taking into account the issue of individual support to artists and designers.

Don’t get me wrong, it is not my intention to rain on the Rijksmuseum’s parade or to spoil the festive mood around their Grand Opening. On the contrary, I too congratulate the Rijks, the city of Amsterdam and the Dutch citizens with their renewed Museum of the Netherlands. The only thing I hope to achieve with this text is a small shift in the general perception.

The image that seems to arise – enhanced by well-oiled publicity campaigns – is that everything is hunky-dory again in the land of the arts, now that these large, prestigious, top-of-the-bill institutions on the Museumplein have reopened their doors. This positive yet partial view is attractive in many ways: small businesses from the neighbouring Spiegelkwartier praise the Rijksmuseum in anticipation of a growing number of potential customers; the city looks forward to increasing revenues for the so-called cultural infrastructure (hotels, restaurants and tourism) and will invest another € 3 million in City Marketing together with the museums, on top of an annual budget that already exceeds € 12 million, according to the New York Times’ calculations.

There is no way the smaller institutions can top this. And normally, they are not expected to. But the issue here is perception, and the ease with which the supposed success of one can be used against others. I can already hear the assembled politicians say: ‘Isn’t Dutch art just thriving? Look at the Museumplein, long cues, more than 30.000 visitors!’

It is a picture which The Hague likes to support: high visitor counts + plenty of media attention = success. The picture seems to justify the idea that, with investments only in the upper segment, ‘the rest’ will be fine. But what is easily forgotten here, is that these top-level institutions have often had decades, if not centuries to develop themselves into successful and prestigious institutes. The unintended (?) side-effect of such a partial frame, is a climate of (self)complacency that hardly leaves any space for institutions who (by choice or out of necessity) opt out of this way of working and thinking. In fact, some institution’s strength lies in developing programmes and projects away from the spotlights, not in plain sight of the mainstream. Which, by the way, doesn’t mean that they lack audiences or appreciation; this value is just quantified differently. Or maybe I should say, cannot be quantified instantly.

In his article for the Financial Times, Simon Schama does not only praise the dynamic layout of the ‘exhilaratingly brilliant makeover’ of the Rijksmuseum, where an active dialogue has been created between the material world and our cultural imagination. He also refers to our historian Johan Huizinga, who believed that books, objects and texts are inextricably connected in the birth of a civilization. If we follow this train of thought, we come to the conclusion that a new master (such as Rembrandt) could never have emerged without the ‘creative force of the milieu’ in which he developed himself. This train of thought is diametrically opposed to the idea of the solitary creative genius or a singular institution; in fact it underlines that context, insertion and a vigorous base are the necessary conditions for a thriving cultural climate. The new layout of the Rijksmuseum mirrors this discourse, as Schama writes. And to that I would like to add: all we need is for The Hague to finally join this discourse.

Christel Vesters is an art historian, critic en curator. This essay is a “Retort” written at the request of Platform Beeldende Kunst. “Retort” is an initiative of Platform BK and aims to direct the debate on art and culture with timely responses to cultural policies and coverage on art in the media.