Precarious Practices #6. Strategies for curating through (and after) Covid.

WE ALL BEGIN life in water

We all begin life because someone breathed for us

Until we breathe for ourselves

Someone breathes for us

Everyone has had someone—a woman—breathe for them

Until that first ga(s)p

For air

– M. NourbeSe Philip[1]

I was reminded of these words, this piece of text, this poem, when it echoed through the voices of Angelo Custódio and Yara Said during their participatory performance Breathing /sites at the Four Sisters garden, project space, labyrinth. As I listened to these words, and re-read them again and again when I got home, I couldn’t help but connect them to this text that I am writing. This text into what it was like to be a curator, to be an organiser of public programs and events, as the pandemic unfolded all around us. The words of M. NourbeSe Philip resonated with me because they carried ideas around the necessity of support systems, of breathing for one another, of infrastructures of care.

In the midst of the pandemic I found myself (and my collaborators) rushing to find places and forms for our exhibitions and programs—live-streaming everything, transforming cancelled exhibitions into online formats, (re)embracing snail mail. Being given the space to write this text has allowed me to look back on my own work over the last months, at how things came into being and how they can inform future practices. My earlier work began in the realm of community organising around socio-political issues, not in art and culture institutions, and I try to carry those practices into what I do today. When I think about what it means to be a curator, I try to link it back to the early etymology of the word itself—a guardian; one who has care or superintendence of something. The word ‘care’, and practices of care, have been heavily permeating the conversations, exhibitions, and programming that I have been seeing take shape in the last few years, punctuated by our present (pressing) moment. This includes books like The Delusions of Care by Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung; the Wxtch Craft cycles from the KABK Stadium Generale; Landscapes of Care from the Copenhagen Architecture Festival; Make yourself at home: radical care and hospitality from Temporary Art Platform (TAP); amongst others.

Looking back at some of the work that I have been doing during the last one and a half years, I want to explore the diversity of what curation as caretaking can mean in different contexts and how it is based on solidarity networks, or maybe on tactical alliances — but in any case, on being interdependent and caring together.

Redistributing Resources

I have a shiny silver sticker on the back of my laptop, from the Feminist Center for Creative Work that says ‘Redistribute Resources’—a constant reminder of the importance for those who have access to resources to think about how these resources are distributed. As cultural spaces began to close during the pandemic, and events and programs got cancelled, it was even more urgent to think about how those of us who still had access to resources could distribute them further. In my own work this happened most clearly at two different moments, for two projects that had already been funded by cultural subsidies.

The first was a small curatorial research project, The Power of Doing Nothing, that I was working on together with Petra Heck. We had received startsubsidie funding from the Stimuleringsfonds to do further curatorial research and write a funding application for the full iteration of the project, which was meant to take the form of a distributed exhibition. The pandemic, and subsequent lockdowns, happened at the moment that we were attempting to give the project more shape and form. Instead of trying to think the project into a distant and uncertain future, we decided to use the funding (most of which was previously allocated to curatorial research and writing hours) to put on two radio shows on Ja Ja Ja Nee Nee Nee, together with Radna Rumping, and invite the artists who we wanted to work with for the exhibition to contribute to the shows.[2] This allowed us to distribute the funding we had received to artists that we wanted to work with, and pay them for their contribution now (at a very financially precarious moment for many people) instead of for potential work in the future.

The second instance of this was with Versal, a former art and literature journal turned independent publisher, that I am an art editor for. Led by Marly Pierre-Louis—with the support of myself and editors Megan M. Garr, Anna Arov, and Jennifer Arcuni—funding that had been received to put on a live event program was instead used to create the VERSO / box, a curated collection of work commissioned from local and international artists, packaged and delivered monthly to subscribers. This shift allowed the money, which had been reserved for a handful of events, to instead be distributed among a much larger group of artists and writers. For me, these two examples make clear the responsibility we have when we get resources to think carefully about their (re)distribution—where it is going, how is it balanced, who needs it most? This responsibility must extend beyond individual curators or organisations to make decisions about how they distribute resources. The subsidy-distributing bodies that I was in contact with, like the Stimuleringsfonds and Letterenfonds, made it clear during the pandemic that if projects had to be cancelled or postponed, it was vital that we find ways to pay artists part—or all—of their fee as soon as possible. This flexibility to shift the scope and form of a project, and the insistence on the importance of paying artists and cultural workers fairly, despite the circumstances, is something that can be taken into our post-Covid future. For example, the Fair Practice Code could potentially articulate proper contract requirements that also give artists rights to a fee for work already completed, even if a festival or exhibition is cancelled.

Providing Access to Knowledge that Is Often Hidden or Unseen

In May of 2020, as systems of financial support for freelancers impacted by the pandemic were being put into place by the government, there was a crisis for non-EU cultural workers whose artist visas could be put into jeopardy by receiving the TOZO financial support.[3] This collective conversation, happening in text message threads and through word of mouth, needed to be made more visible within the cultural sector. Together with a collaborative effort from Platform BK, Salwa Foundation, and W139, we put on the first edition of the Solidarity Sessions. This first event took place inside the hybrid environment created by the group of makers who were working together through the lockdown as part of their exhibition market. The artists turned the exhibition into a communal working station and created the infrastructure to host a ‘public’ event for a large virtual audience very early on in the pandemic. Taking the form of an info-session and open conversation, we looked at the issues that cultural workers, independent exhibition spaces, institutions, and the webs of networks around them were facing in light of the corona-crisis. Joined by cultural workers, a lawyer, and a union representative, we shared personal stories, practical information about possible legal pitfalls in obtaining government support, and made visible what different organisations and platforms were doing to support cultural workers during this particularly precarious moment. The feeling of empowerment that this event generated, through the sharing of knowledge, and the sense of ‘togetherness’ that was felt at a time where people were particularly lonely and alienated from one another, should not be forgotten as we move into (hopefully) less precarious circumstances.

The first Solidarity Sessions in W139, during the exhibition market.

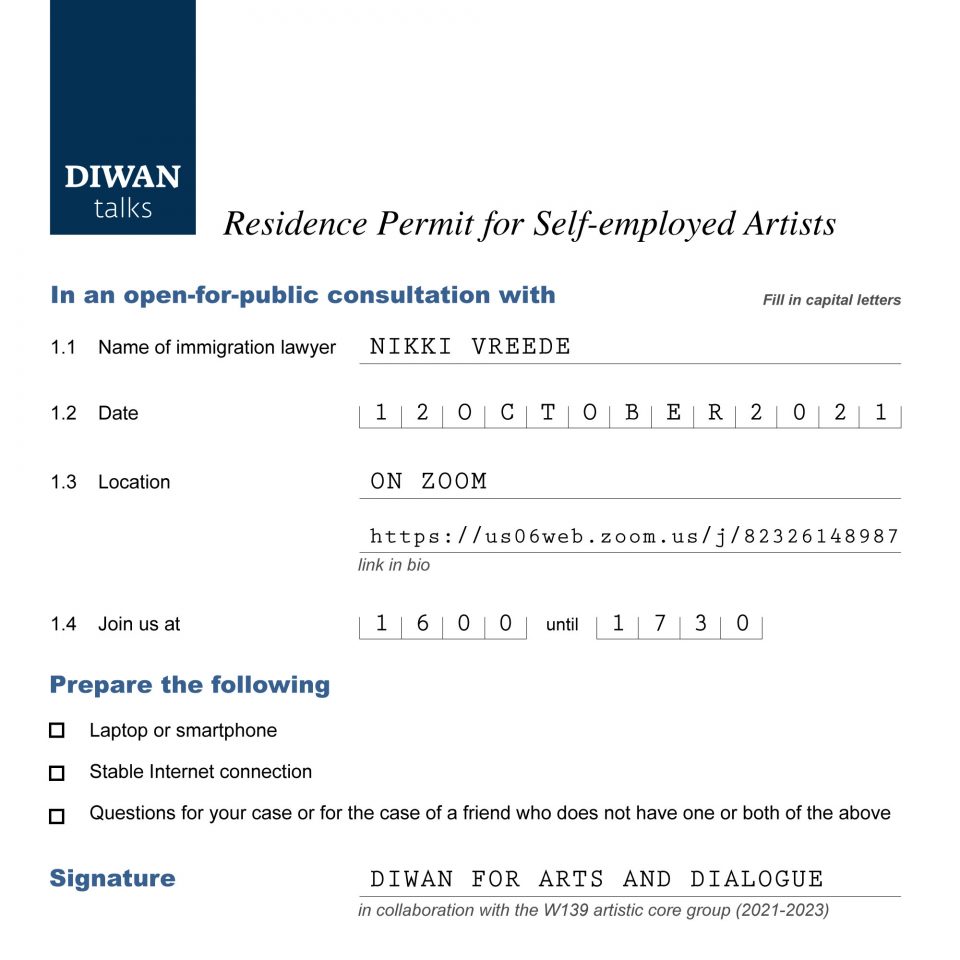

Another initiative that emerged during the pandemic, but had been conceptualised much earlier than that, is DIWAN for Arts and Dialogue, a platform co-initiated by Fadwa Naamna, Hilda Moucharrafieh, Ehsan Fardjadniya, Emirhan Akin, and myself. The aim of DIWAN is to support cultural workers, especially those in the diaspora, in the development of their projects and artistic practices—tackling the collective struggles of residency permits, housing, and project funding, amongst others. The first DIWAN event was aimed at mapping and understanding the particular urgencies and issues that postgraduate artists and cultural workers confront in the first years after their graduation. In an informal and collective setting, we invited people to share their own experiences, with the belief that openly sharing and discussing these struggles can be an effective tool to navigate and confront our challenges, while supporting one another. With DIWAN, and these other initiatives, it is about looking at all the different layers and infrastructures that support and bring cultural programming into being—artist visa support, affordable studios and housing, fair fees for cultural workers, subsidised education—and not only that which manifests visibly at the moment of an exhibition, an opening, a public event. In these cases the Covid crisis—which exacerbated and made visible precarious circumstances—was the catalyst of initiatives that will extend well beyond the present moment.

On the Agility of Smallness

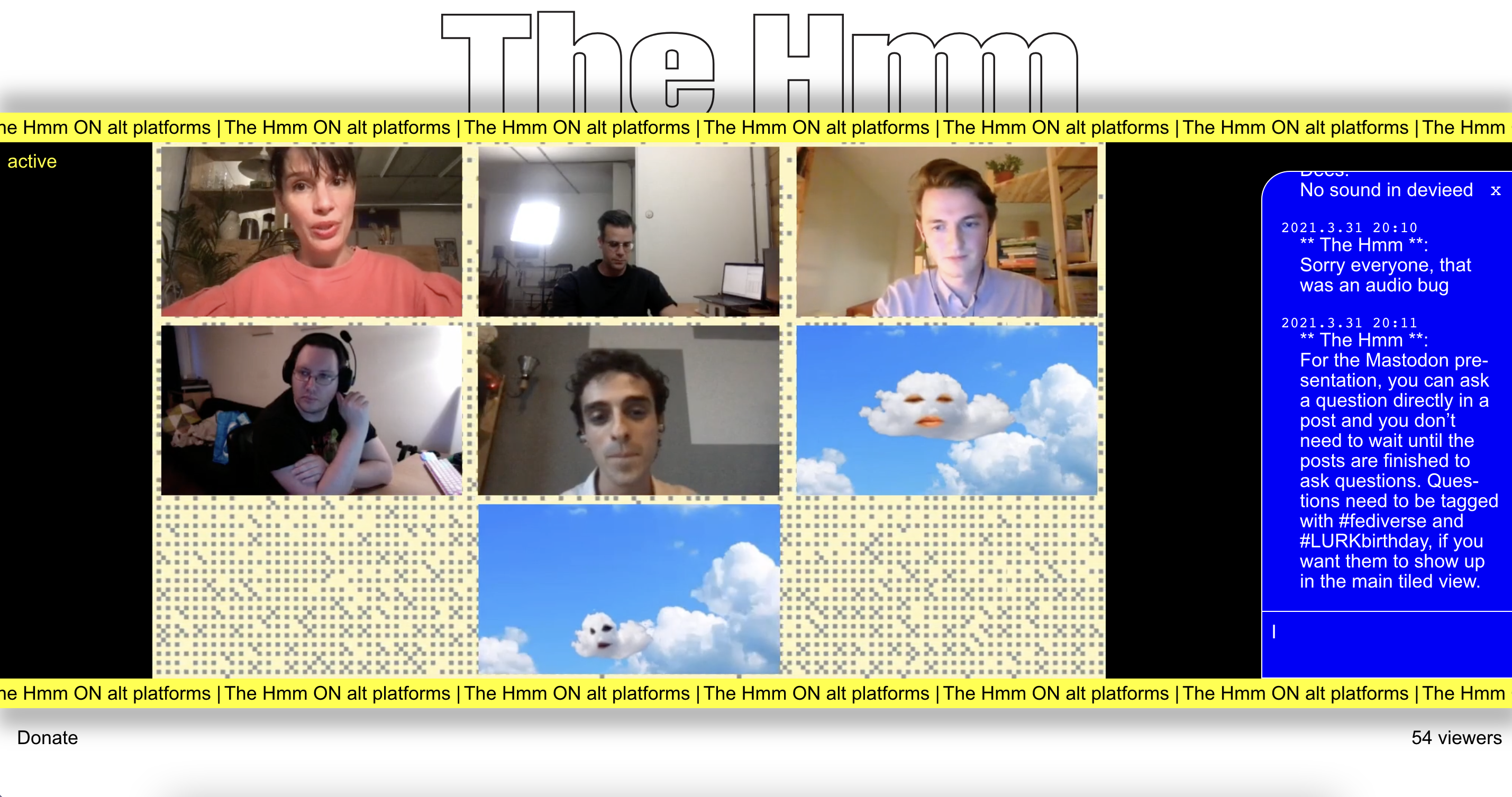

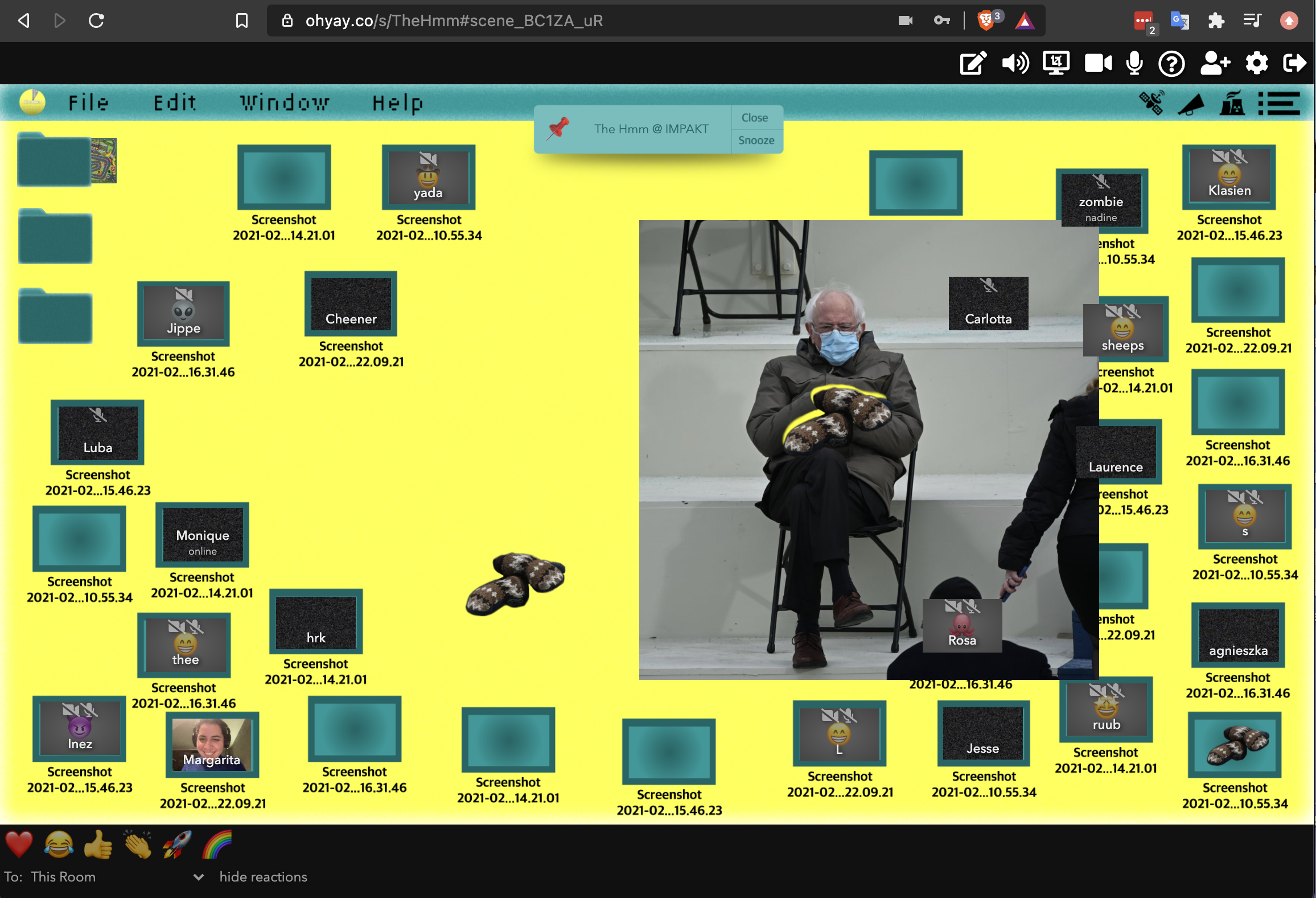

During the pandemic, particularly with my work with The Hmm, a platform for internet cultures, I was busier than ever. With The Hmm, our events were focused on bringing online culture offline and to a physical space. Once we could no longer be together in a physical space, me and my colleague Lilian Stolk had to think about what it meant to be online together, reflecting on internet cultures, when everyone was exhausted from being online. We knew how to welcome our guests and our audience in a physical space, but how does this manifest online? Rather than focus on the limitations of being in an online space, we started to think about its potentialities. In our first experiment we did an edition of The Hmm where we jumped from one platform to another (from Twitch to Jitsi to Zoom), with a different speaker on each platform—researching what the best platform was for cultural events. It turned out it was none of them, so together with Hackers & Designers we built a shared livestream platform, away from the extractive practices of Big Tech.[4]

We did tours through alternative platforms like Mozilla Hubs and Ethercalc, and had a hybrid event at MU where our physical guests were linked together with virtual buddies. We learned about the extra time, care, and communication we need to put in in order to make a successful online event, but also about the potentialities that are inherent in the online space. Being online allowed us to welcome speakers and an audience from all over the world, which we were not able to do with our small budget for physical events. Online events also allow people who normally would not be able to join a physical event, for whatever reason, to take part. With increasingly sophisticated closed captioning technologies, online events can be more accessible than their physical counterparts.

Finally, in the process of organising events with The Hmm, we learned the value of being a tiny organisation. Because of our small size we were able to respond more quickly to the changing conditions created by the pandemic, and we were able to be more flexible and agile in collaboratively creating our experimental online spaces away from Big Tech. To me, this period with The Hmm signalled how care manifests in the spaces we build to be together with one another (that our data does not have to be extracted to take part in an online event); in how we communicate with our audience and speakers (doing a lot of tech tests, having moderators for the chat and the speakers, sending clear event info emails); and in continuing to work with hybrid events because of the accessibility they offer to a wider audience.[5]

Infrastructures of Care

In the summer of 2019, I was in Belarus in Minsk (where I was born) with my parents and my partner. We spent an entire day going from one graveyard to another, cleaning the gravestones of my grandparents, great grandparents, uncles, aunts. What resonated with me was this notion of taking care, of sweeping, dusting, pulling back the plants that have overgrown—this work of intergenerational maintenance. And so again I go back to these infrastructures of care; to see care, support, and solidarity with one another as something that is active. As something that needs to be maintained, by institutions, organisations, and communities. As something that we need to feel a deep sense of responsibility for, but also hold one another accountable for. For me, curating is a practice that takes into account everything around the exhibition itself—the infrastructures of financial support, the organisational structures within institutions, the support systems available for cultural workers. How do the structures that we’re embedded within, and which we sustain and shape, reflect on the questions that we are engaging with? How do we sweep, dust, pull back the overgrown plants?

References

[1] M. NourbeSe Philip, ‘The Ga(s)p’, in Poetics and Precarity, ed. Myung Mi Kim and Cristanne Miller (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2018), pp.31.

[2] The two shows were ‘Listening to ~ the power of doing nothing’ and ‘A conversation on ~ the power of doing nothing’ which you can listen to here (https://jajajaneeneenee.com/shows/listening-to-the-power-of-doing-nothing/) and here (https://jajajaneeneenee.com/jn/shows/a-conversation-on-the-power-of-doing-nothing/)

[3] You can read more about the full situation as it was happening, as outlined by immigration lawyer Jeremy Bierbach, on the website of Franssen Advocaten: https://www.franssenadvocaten.nl/english/tozo-and-self-employed-residence-permit-holders-the-latest-summary/

[4] The code for the livestream platform is available on Github and we setup a MIT license for its use: https://github.com/hackersanddesigners/the-hmm-livestream

[5] See The Remote Access Archive project for an online archive of the ways disabled people have used remote access before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: https://www.mapping-access.com/the-remote-access-archive

Margarita Osipian is a researcher, curator, and cultural organiser living and working in Amsterdam. Engaging with the intersections and frictions between art, design, technology, and language, she organizes collaborative projects in formal institutions and more precarious and fleeting spaces. Holding an MA in Media Studies from the University of Amsterdam and an MA in English Literature from the University of Toronto, her research has focused on visual culture, technology, and the carceral state. Margarita is part of The Hmm, a platform for internet cultures, a member of the Hackers & Designers collective, on the curatorial team of Sonic Acts, and part of the artistic core of the W139.