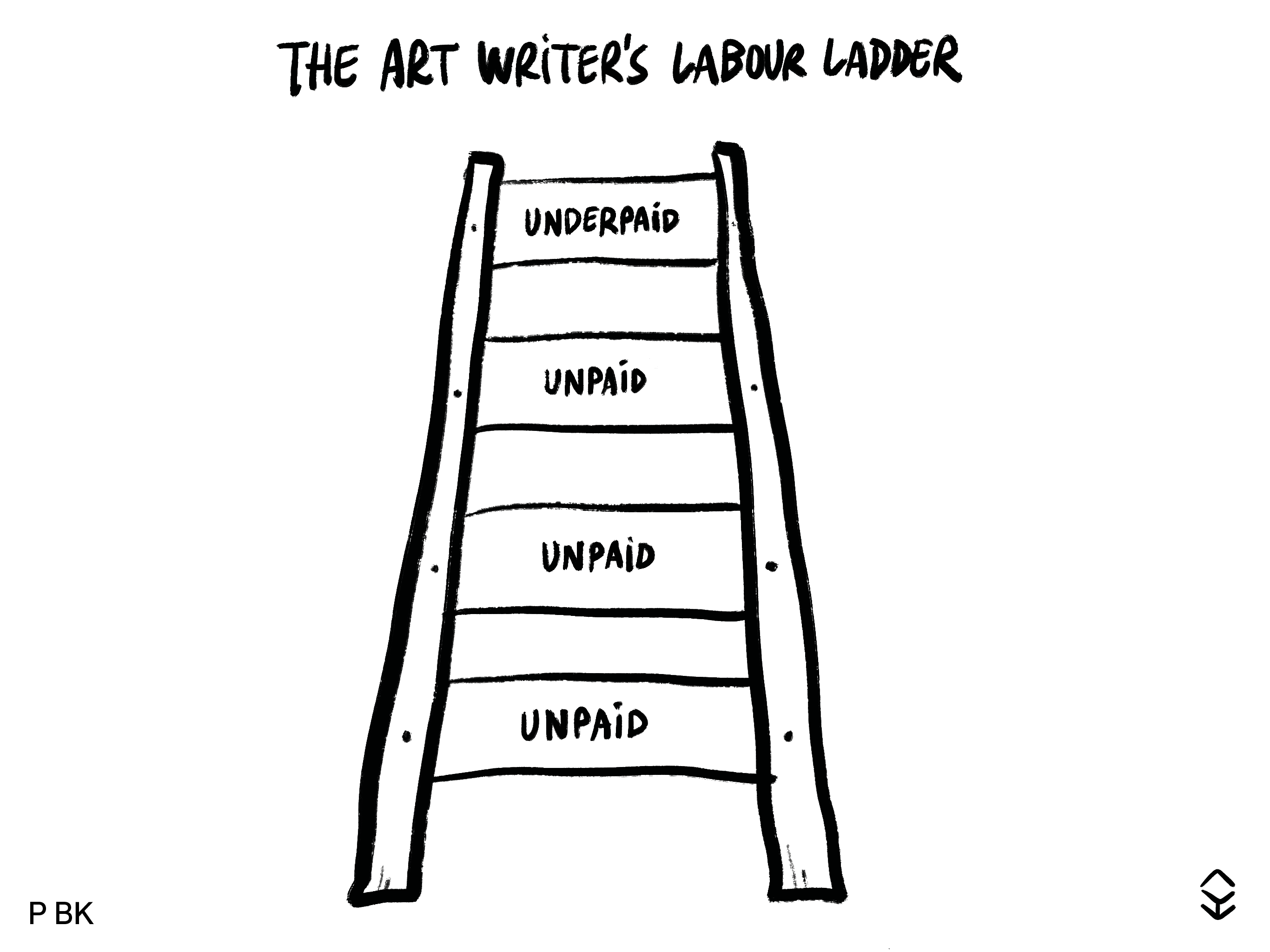

Art writers know: art writers are underpaid. What makes fair practice in this field so elusive? Where is the system failing, and what can we do better?

In the Netherlands, writing articles for print and digital publications based on one’s own ideas is a VAT-exempt activity.[1] When I told a friend about this, she joked, “Wow, writers have it worse than artists; the tax office thinks you earn so little that it doesn’t even bother taxing you!” Art writers are underpaid; this is a widely acknowledged problem among those who write. Yet conversations on this subject only take place in informal exchanges—between friends and colleagues, in cafes, and over text messages. Fair practice for art writers has not been addressed in public discussions, which this article seeks to change.

To shine a light on this issue, I have looked into the current system for art writers in the Netherlands. I focus on freelance writers and apply the term “art writer” broadly: it includes art journalists at daily newspapers, contributors at art magazines, and writers who work on content for art institutions. Is it possible for a freelance art writer to make a living from their writing under the current conditions? What makes fair practice in this field so elusive? Where is the system failing, and can we do better? My investigations reveal a system that requires sober reflection on transparency and funding policies.

The Art Writing Economy

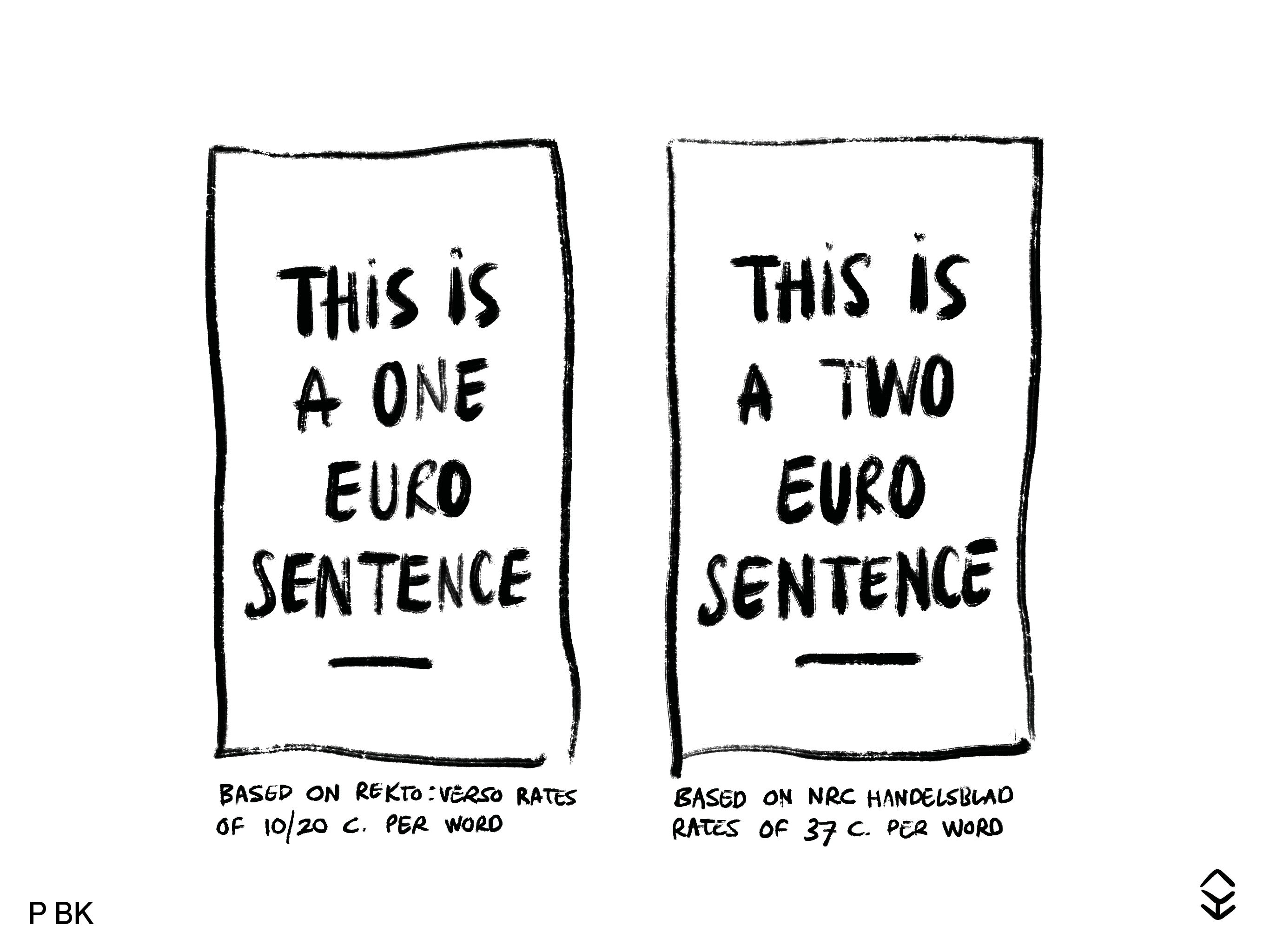

To begin, let’s consider the current rates for an art writer at a selection of Dutch and Flemish newspapers and art publications. Rekto:Verso, a Flemish magazine, pays 2.5 cents per character (which equates to approximately 10-20 cents per word) and a ceiling of €250 for web pieces.[2] De Witte Raaf, another Flemish publication, uses the same pay standard as Rekto:Verso. Het Parool, the Amsterdam regional newspaper, has a rate of €150 for a short review (300 to 450 words) on the arts, film, or theater and €220 for a book review. For longer pieces, Het Parool pays 22 cents per word.[3] The Dutch national newspaper NRC pays a minimum rate of €150 per assignment and a minimum rate of 37 cents per word for starting journalists.[4] Museumtijdschrift, one of the biggest art magazines in the Netherlands, pays 37 cents per word for print and €200 for a web article. Metropolis M pays 25 cents per word for its print magazine.[5]

Whether the rates quoted above amount to a livable wage does not depend solely on the numbers, but also on how long it takes to produce an article and how many articles a freelance writer gets assigned per month. While an efficient writer can write a short review in the span of one afternoon (although they also need time to consume the exhibition or film they are reviewing), a long article or essay might take weeks to finish.

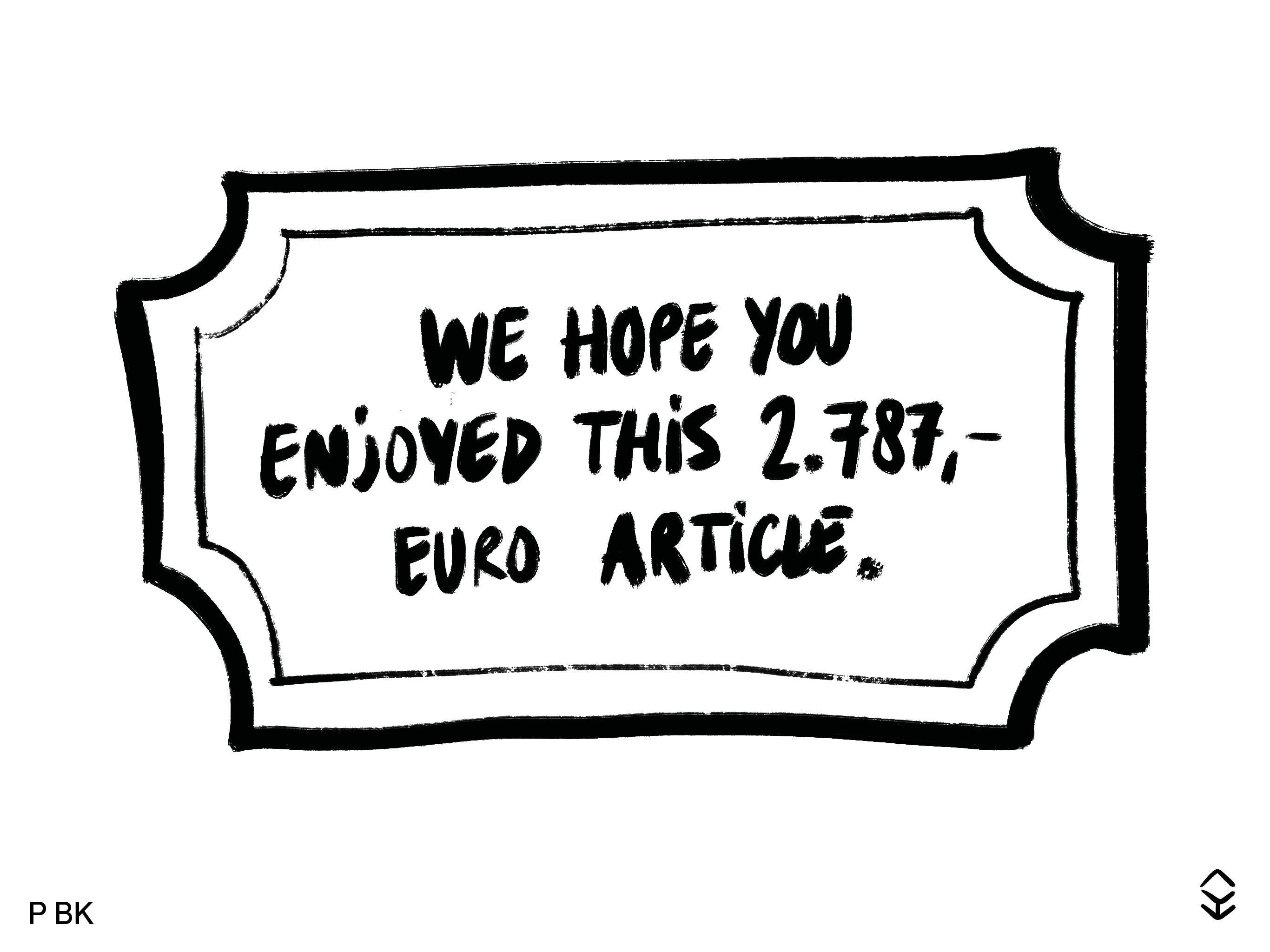

I will use this longform article as an example to demonstrate the labor involved. My work has involved researching the literature and websites, meeting with Platform BK editors, coordinating interviews with sources, preparing talking points, traveling to sites, having hour-long conversations, and fact-checking. Back at my desk, I summarized notes and synthesized key points—write, edit, repeat. The overall word count of the resulting article is around 3,700 words (excluding footnotes). The number of billable hours is 80, which averages to 16 hours per week for five weeks.[6]

In alternative scenarios, I would receive around €580 if I published this article in Rekto:Verso or De Witte Raaf and €814 at Het Parool. At NRC, using its minimum rate, I would get €1,369. Other art-writing outlets would pay a rate similar to or between these sums. Thus, to return to my first question: is it possible to make a living as a freelance art writer under the current conditions? The answer is not really. One can only realistically make a living from writing if 1) one writes for a large newspaper or magazine and gets regular assignments and/or 2) one can apply for (and receive) funding for new projects consistently. Both options are tall orders, to say the least.

References to Fairness

While these numbers allude to a grim reality, there has been no shortage of guidelines concerning fair pay in the culture sector. For artists and art institutions, the establishment of a guideline for artists’ fees (kunstenaarshonoraria) has made payments for artists more workable.[7] De Zaak Nu, the association for Dutch presentation and post-academic cultural institutions, has published a guide for curators and facilitators on fair rates for both employed and freelance positions.[8] DigiPACCT, an initiative by Platform ACCT (Platform Arbeidsmarkt Culturele en Creative Toekomst, Platform Labor Market Cultural and Creative Future), provides references on collective labor agreements (cao’s) in the cultural sector (e.g. for museums and art education) and a calculator for freelancers to estimate reasonable rates for their work.[9]

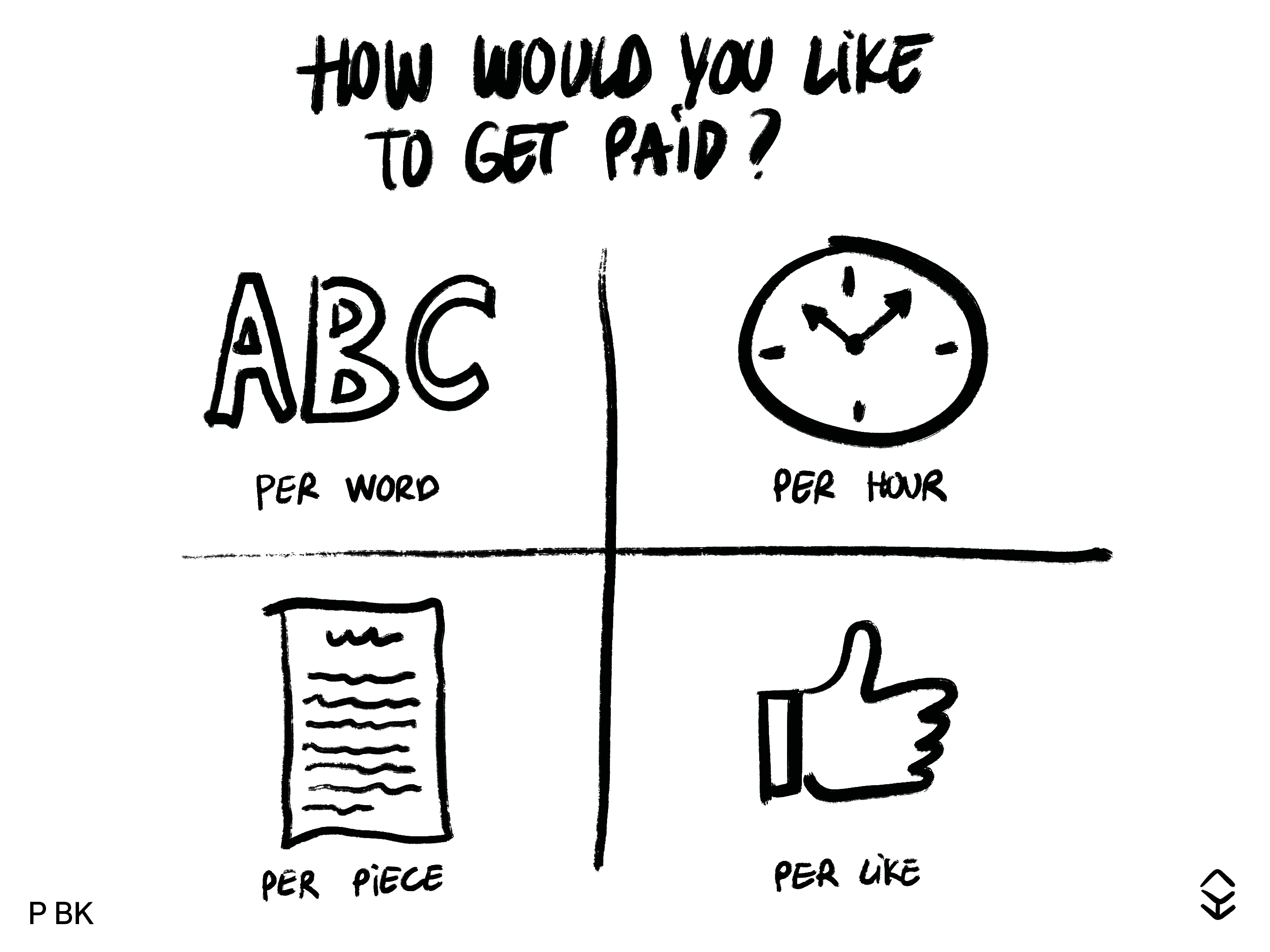

For art writers, the closest thing there is to a guideline is a new work code for freelance journalists agreed upon between the Nederlandse Vereniging van Journalisten (Dutch Association of Journalists, NVJ) and DPG Media, the company that owns Het Parool and De Volkskrant, among other publications. Under this code, freelance journalists working for DPG enterprises are entitled to a minimum hourly wage of €30 and indexation of all rates. The main purposes of the work code are to “remove the negative effects of current market forces” and to “link the [freelance] rates to the collective labor agreement wages.”[10]

The NVJ website, like Platform ACCT, provides a calculator for freelancers to decide their hourly rate as derived from the collective labor agreement for publishing companies (cao voor het Uitgeverijbedrijf).[11],[12] NVJ advises that freelance writers should be paid more than salaried writers in order to cover social security and administrative overhead.[13] Concretely, this means 150% of the salaried amount (167% if holiday allowance is included).[14]

Although the work code and the calculator are instructive, they come with limitations. First, it is unclear how the code will be applied. Even though NVJ asks freelancers to report noncompliance with the code and will carry out an evaluation next year, there is no guarantee the code will deliver on its promise. In fact, when I spoke with writers and editors about the new work code, most of them were doubtful about how useful it would be. Some suggested that similar pay standards had been put in place in the past but were not consistently applied. Second, the work code only applies to DPG Media. No agreement has been reached with art magazines or with Mediahuis, the company that owns NRC and De Telegraaf.[15]

Lastly, the shift from “per word” to “per hour” requires a reframing of labor and leads to ambiguities in implementing the work code. A writing project that takes weeks to complete, when calculated per hour, becomes much more expensive than it would be with the per-word rate. While this conversion exposes the underlying unfairness of current pay schemes, it can make pay negotiations difficult for writers. Here is my attempt at using the NVJ calculator to determine a rate for this article: first, I determine my hourly rate, which would be €34.84 based on cao scale 7. I then count 80 billable hours for this article, as stated in the previous section. Multiplying the numbers, I get a result of €2,787. This would be fair payment and, in fact, aligns with what I actually received for this article—thanks to support from the Mondriaan Fund.[16]

Why Don’t Publications Pay More?

“If newspapers and magazines [paid] what NVJ suggests, I think that a lot of newspapers and magazines [couldn’t] be made anymore,” said Marina de Vries, editor-in-chief of Museumtijdschrift. As a commercial magazine, Museumtijdschrift generates revenue from advertising, subscriptions, and sales. The magazine has never relied on funding for its operations (except for the Tentoonstellingsprijs, a separate program it organizes, which receives funding from the Prins Bernhard Cultural Fund). In De Vries’s words, the magazine is “made for the readers” and paid for by them, which makes it “financially independent.”[17] The revenue margin left over after production and operation costs is small.[18] I asked De Vries what the priority would be should the magazine’s revenue increase, for example through sales. “We would first add a member to our team and then consider pay [for] authors,” De Vries said, though she emphasized that the scenario I proposed would be difficult to realize.

If increasing writers’ pay comes last for a big commercial art magazine, it is not hard to imagine how this works at smaller publications. After the budget cuts by Halbe Zijlstra in 2011, art magazines lost structural funding. As journalist Steffi Weber reported for NRC in 2013, all art publications were expected to run on a commercial model, while the overall market for advertisements from art institutions and subscriptions from art professionals shrank.[19] In 2014, the critic Roos van Put concluded that independent art magazines essentially survive on “passionate volunteers and a few (modestly) paid staff.”[20]

In response to the budget cuts: the publication Mister Motley, which used to run a print magazine, switched to being online only.[21] Metropolis M reduced its team size, with the remaining staff taking on more work. According to its editor-in-chief Domeniek Ruyters, it was not until the magazine gained more income from advertisements that Metropolis M was able to hire additional editors on a freelance basis. In 2017, the so-called “ban on government subsidies for art magazines” ended.[22] In 2019, some funding became available for art magazines through the Mondriaan Fund.

However, “The system of funding changed almost overnight in 2021,” said Daniël Rovers, editor at De Witte Raaf. “Since the beginning of 2022, these funds are only for additional initiatives and programs, and do not support operational [costs] (such as the editing of texts, without which a magazine could just as well be a personal blog) or production costs of the publications.”

In our conversation, Renée Steenbergen, freelance journalist and author of books on culture policies, raised a good question: “Why can’t the publications facing budget cuts choose to produce less and pay [their authors] more?” When I paraphrased this question to Domeniek Ruyters, he responded, “On the contrary, [instead of] producing less, when the funding went away, we had to produce more in order to survive as a magazine.”

This explains the catch-22 situation for smaller (and more critical) publications. On the one hand, they are expected to become a product for the market, often with minimal staff. On the other hand, they need to maintain a voice that is not entirely driven by the market. Despite providing crucial platforms that activate discourses on and through art, the market share of these publications remains narrow. Even though they have received temporary and project-based funding to develop new programs, the budget does not affect pay for writers—at least not directly.

Who Can Afford To Be an Art Writer?

Through my interviews, I discovered that practically all freelance writers take on a second (and sometimes third) job. For example, one writer does curatorial research for a museum. Another works on grant applications for artists, which pays €50 per hour. Julia Steenhuisen, coordinator of the Prize for Young Art Criticism (Prijs voor de Jonge Kunstkritiek, PJKK for short), confirmed this observation: “For those who submit to the prize, art criticism does not seem to be their main focus. Most of them have hybrid jobs such as curator or teacher.” The situation is not new. “In my experience as a freelancer,” said Marina de Vries, now editor-in-chief at Museumtijdschrift, “this has been the case since the ‘90s. Back then it was not uncommon for a writer to be supported by the income of a partner.”

The PJKK, which started in 2008, is a biannual prize for those under 35 writing art criticism in the Dutch language, sponsored by several Dutch and Flemish art institutions and the Mondriaan Fund. Though the prize tries to encourage young people to join the arena of art criticism by handing out a cash prize of €3,000 and assignments from its media partners (including, for example, Het Parool and Metropolis M), the long-term prospects for art writers remain bleak.

In an internal survey of 28 recipients of the prize from 2008-2018, most agreed that being awarded the PJKK had led to an increased number and frequency of assignments. Many, however, said they did not know or did not agree that the prize gave rise to higher pay. “If you are still here at the end of [this writing career], perhaps you will get a decent rate. Having a PhD doesn’t lead to more pay,” said Renée Steenbergen. Alongside her freelance writing for NRC, for which she is paid 42 cents per word, Steenbergen makes a living by writing books, giving lectures, and taking on advisory roles at cultural institutions.

Given the various guidelines listed earlier in the article, one would think it would be possible for a “hybrid” writer to charge accordingly: referencing De Zaak Nu when writing for art institutions and the NVJ calculator when writing for newspapers. However, the real situation is far removed from the one envisioned in the guidelines: writers receive a low rate without much room to negotiate.

In his essay “New Perspectives for Art Criticism” (“Nieuwe perspectieven voor kunstkritiek”), freelance journalist Edo Dijksterhuis traces the deteriorating working conditions for critics: with art criticism decreasing in newspapers and magazines and with print publications becoming more obsolete with each new generation, traditional media has replaced critics with general reporters and substituted freelancers for salaried staff.[23] For-profit newspapers do not have an interest in raising writers’ pay. “Newspapers have become [businesses] where profits basically go to the shareholders,” said Renée Steenbergen. “When I started at the newspaper in 1987, payment was alright. However, since then it has gone down more and more, and never up again.”[24]

A freelancer who wants to charge a fair rate is faced with prevailing underpayment. If they raise questions about their fee, they risk losing projects to those who are willing to accept lower pay, which provokes a further inquiry: What makes a writer accept lower pay (or even no pay at all)? One writer I encountered in my interviews provided a glimpse into the answer. Thijs Lijster is a professor at Groningen University and was the recipient of the PJKK in 2010. He has written prolifically about the role of art criticism/critics and the precarious labor relations in the cultural sector.[25] As an academic, his main income comes from the university. In our conversation, he said half-jokingly, “It is people like me who are messing up the market.”

Indeed, anyone who can afford to write for a low fee or for free contributes to a market hostile to those who cannot. In the arts, people often convince themselves and others that working for pay is not as important as working out of passion, expressed in sentiments such as “Work because you like it, not because you want to get rich.” Yet, without fair pay—which does not equate to “getting rich”—passion leads to burnout, perpetuates (self-)exploitation, and glorifies those with enough privilege to keep working for free.[26]

The rhetoric of passion is further fueled by publications built on free labor. For instance, Kunstlicht, a volunteer-run academic journal on the arts, visual culture, and architecture declaims that the journal is “not able to provide an author’s honorarium; time is compensated with time.”[27] Tubelight, which publishes in print four times a year (available for free in over 200 galleries and art institutions in the Netherlands) and maintains a website, is “created entirely without remuneration.”[28] Even with the best intentions, the practice of working for free justifies (self-)exploitation and complicates—or rather, dilutes—the discussion on fair pay.[29] As long as the cycle continues, and as long as enough people internalize that free labor is acceptable and even desirable, it will be difficult to achieve fairness and improve negotiating power for freelance writers.

What about Individual Grants as a Way around Low Pay?

Given the absence of fair pay in the sector, independent writers might try to get funding to supplement their income. Currently, such funding comes from two sources, both of which are project-based. The first is the Curator Researcher (Curator Beschouwer) scheme from the Mondriaan Fund, which “supports curators and mediators [author’s note: this includes art writers] with new visions and narratives that fulfill a key role in connecting visual art and cultural heritage with the public” by providing €2,050 per month for a maximum of 12 months.[30]

The second source is the Dutch Fund for In-depth Journalism (Fonds Bijzondere Journalistieke Projecten, FBJP for short), which provides funding for “individual journalists for articles, long-reads, photo reportages, journalistic books/biographies, and investigative reports (tv, radio, online, print)” up to €2,500 per month.[31] (The Kunst Media scheme from the Mondriaan Fund, from which I received support, was a temporary measure from late 2021 to early 2022 and was open to project proposals from both individuals and platforms. It is unclear if/when this scheme will be run again, or whether it will stay in the same form.)[32]

Any individual who has applied for funding knows that writing an application can be a full-time effort with an uncertain outcome. Apart from the time-consuming grant writing process, the funds’ evaluation criteria require demonstratable experience. The Mondriaan Fund assesses applicants based on records of “publications, exhibitions, research, and/or other projects” and FBJP asks for “a contract for [the author’s/journalist’s] story or book to be published or broadcast in Dutch.”[33]

These prerequisites pose a chicken-or-the-egg dilemma for those who are less experienced. In trying to build their CV, less-experienced writers look for publication possibilities and come across assignments based on free or underpaid labor. We see here in action another common justification for working for free: that it brings social capital—a better reputation, network, and future opportunities—that might eventually result in financial compensation. Writing for free is not necessarily the writer’s choice, but in the current system, they have to engage with this process in order to gain access to funding.

A Few Conclusions: Transparency as professional practice and funding as a guide for a healthy sector

When I started my research for this article, I noticed the recurring discussions around the future of art criticism in the Netherlands.[34] I find researcher Ingrid Commandeur’s summary to be the best explanation:

Criticism itself is migrating […] to the internet and social media; to self-published magazines by artists; to the spectator, as witnessed by the blurring of the boundaries between the professional and the amateur; and last but not least to the proliferation of symposia, publications, reading groups, and discussion forums in the art world […] If you look at [the diagnosis of “the crisis in art criticism”] from a different angle, suddenly it seems there is a lot of potential…[35]

As my investigation unfolded, I saw writers adapting to hybrid professions. Yet rather than fulfilling the potential of art criticism—in form, content, and format—many writers become hybrids because they cannot afford to write otherwise. Big newspapers make money for their shareholders while overlooking freelancers’ pay. Independent publications are operating with margins so small that they cannot pay writers what they deserve, despite being aware of the problem.

As writers, we can collectively challenge the rampant exploitation in the field: call it what it is, be aware of the field guidelines, and be transparent about actual payment and work conditions. It took several lawsuits between DPG Media and freelance journalists who accused them of unfair pay before the negotiations over the new work code was settled, but we cannot solely rely on the few brave writers willing to risk their careers.[36] “There is a baffling lack of solidarity between editors in permanent employment and their many freelance colleagues,” said Renée Steenbergen. “To be effective in changing freelance rates, those in permanent employment too should stand up and support [their] freelance colleagues.”

For aspiring writers, cultivating non-exploitative professional practices should start with education in art, art history, and cultural studies. An open letter from Platform BK to art academies calls for urgent changes at educational institutions—especially at the administrative and managerial level—so that students become aware of “their professional future [and] how to shape it.”[37]

However, even as writers acknowledge the problems of free and underpaid labor in public, the responsibility of shifting the market or the sector’s mindset towards fair pay does not lie with the individual. While commercial content and publishing outlets can function with income generated from sales, analytical and critical content do not have a market value that would remunerate the author fairly. This raises a fundamental question: is art writing something to be left to the market, as it has been for the past 10 years, or are some forms of art writing a public good that deserves public funding to make fair pay possible?

When it comes to creating a fair funding chain, public funding is more than merely financial support—it guides and shapes the health of the whole sector. One precedent where public funding has had a corrective effect on fairness is the recent Experimental Rules on Artists’ Fees (Experimenteerreglement Kunstenaarshonoraria), which allocated a budget for artists’ fees for art institutions to request (via the Mondriaan Fund) and distribute. As reflected in the evaluation report commissioned by BKNL, this budget allows for fair pay for artists and is crucial for maintaining fair practice.[38] In the case of art writers, publications are the equivalent of what art institutions are to artists. Hence, one way to enforce fair pay for writers is to dedicate part of the budget to the art writer’s fee, which can be distributed at the publication level.[39]

Art writers are preoccupied with their precarious existence. Though governments and funds try to propagate fair pay for everyone in the cultural sector, the implementation remains vague. The market as it is now is unfair; if everything is left up to the market, the exploitation-based cycle will continue. Simply having guidelines does not lead to their implementation. Without a committed budget, fair pay is only fair on paper.

Thanks to all the writers, editors, and coordinators I consulted for their generous contributions of time and insights: Alix de Massiac, Sandra Smets, Daniël Rovers, Julia Steenhuisen, Thijs Lijster, Jan Pieter Ekker, Zoë Dankert, Renée Steenbergen, Domeniek Ruyters, and Marina de Vries.

All illustrations in this text were made by Yuri Veerman.

This article has received support from the Mondriaan Fund.

Footnotes

[1]See: https://www.belastingdienst.nl/wps/wcm/connect/bldcontentnl/belastingdienst/zakelijk/btw/tarieven_en_vrijstellingen/vrijstellingen/vrijstelling_voor_componisten_schrijvers_cartoonisten_en_journalisten. As this article is written in English, citations from documents and articles written in Dutch have been translated and paraphrased by the author. Direct quotations are noted with the original text in the footnotes.

[2] See: https://www.rektoverso.be/p/schrijf-voor-rekto-verso.

[3] As confirmed by Jan Pieter Ekker, the editor of the arts and culture section at Het Parool, all amounts have been increased (indexed) by 2.9% as of 1 July 2022 and will be increased again by 2.3% in March 2023.

[4] This rate was published in NRC’s own article about the recent negotiations about pay for freelance journalists. See: https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2022/04/06/uitspraak-over-perstarieven-kan-begin-zijn-van-meer-zaken-a4108727.

[5] Other than that of NRC, the rates were confirmed by the editors at the respective publications.

[6] I have used a more conservative time estimate. The hours I have not counted as billable include general admin (such as organizing receipts from interview trips) and research/reading/writing time that turned out to be less relevant to this particular subject. A more liberal estimate would be 95+ hours.

[7]See: https://kunstenaarshonorarium.nl/. Note: Paying artists with extra budget from the government has become more common practice in recent years. More on this in the last section of the article.

[8] The guide is available as a PDF at: https://www.dezaaknu.nl/downloads/220110_Richtlijn_functie_en_loongebouw_indexatie_1_jan_2022.pdf.

[9] See: https://www.digipacct.nl/cao-loon-naar-zzp-tarief/.

[10] “De Werkcode is vooral bedoeld om de negatieve effecten van de huidige marktwerking weg te nemen. Daarnaast zullen door de koppeling van de tarieven aan de cao-lonen de freelancetarieven altijd meestijgen met de salarissen van journalisten in vaste dienst.” See the FAQ on vulnerable freelancers vs. established ones: https://www.nvj.nl/themas/ondernemerschap/werkcode/veelgestelde-vragen-over-dpg-werkcode.

[11] Read details of the cao Uitgeverijbedrijf at: https://www.uitgeverijbedrijf.nl/cao/cao_ub_deel_2/pages/default.aspx?tab=0.

[12] See: https://www.nvj.nl/themas/ondernemerschap/tarief/nvj-tarievencalculator.

[13] Similar advice for paying freelancers more than salaried positions can be seen in De Zaak Nu and Platform ACCT.

[14] See: https://www.nvj.nl/themas/ondernemerschap/werkcode/werkcode-dpg-media-zo-reken-je-minimumtarief-jouw-tarief.

[15] See: https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2022/06/02/hogere-tarieven-voor-freelancejournalisten-bij-dpg-media-vanaf-juli-a4131309.

[16] This project, consisting of multiple long-form articles on the “gaps” in fair practice, has been funded by the temporary Kunst Media scheme from the Mondriaan Fund. It contributed 90% of the project costs. Including the contribution from Platform BK and deducting research and travel expenses, I eventually received about €6,600 for this project, which amounts to €2,200-€3,300 (depending on the final number of articles).

[17] According to De Vries, the audience of Museumtijdschrift is older (i.e. with time and money to visit museums) and consists of more women than men.

[18] The Museumtijdschrift team consists of two full-time editors, one part-time web designer, one freelance art director, and freelance writers. One person from the magazine’s publisher, W Books, does the marketing.

[19] “Bovendien treffen de bezuinigingen ook nog eens indirect de bladen: kunstinstellingen adverteren minder vaak nu zij getroffen zijn door de bezuinigingen. Ook abonnees, meestal beroepsmatig gelieerd aan de kunstwereld, krijgen minder inkomsten.” See: https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2013/02/27/bezuinigingen-raken-kunstbladen-dubbel-hard-1213539-a84358.

[20] “Zonder gepassioneerde vrijwilligers en een paar (bescheiden) betaalde krachten zouden geen van deze bladen in de toekomst kunnen blijven bestaan.” Roos van Put, “Vrijwilligers met passie houden cultuurbladen levend”. https://catalogus.boekman.nl/pub/P16-0044.pdf.

[21] See the “History” section at: https://www.mistermotley.nl/over-mister-motley/.

[22] However, at the time of the announcement in 2015, a spokesperson from the Mondriaan Fund did not see a way to free up any budget to support the magazines. “Een woordvoerder: ‘In deze cultuurplanperiode is liefst 35 procent gekort op ons budget voor beeldende kunst en cultureel erfgoed. Op dit moment zien we niet hoe we geld voor tijdschriften kunnen vrijmaken.’” See: https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2015/06/24/nederlandse-kunstbladen-inventief-1508085-a351055.

[23] The article appears in Boekman Magazine 106, an issue focused on art criticism. Read more at: https://www.boekman.nl/tijdschrift/boekman-106-de-nieuwe-kunstkritiek-2/.

[24] Steenbergen added, “By underpaying the enormous [number] of freelancers newspapers are dependent on, they undermine their own position and therefore damage independent journalism.”

[25] For an overview of Thijs Lijster’s book on precarious labor relations, Verenigt U!, see his interview from 2020: https://www.theaterkrant.nl/nieuws/thijs-lijster-als-je-de-kunsten-nu-laat-verdorren-komen-ze-niet-zomaar-terug/.

[26] The podcast series Werktitel by Alix de Massiac and Zoë Dankert illustrate the exploitation and self-exploitation that predominate in the cultural field through interviews. Episode 4 specifically talks about burnout. Listen to the episodes (or read the English transcript) at: https://www.werktitel.org/.

[27] Kunstlicht is affiliated with the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam and operates as an autonomous foundation. See: https://tijdschriftkunstlicht.nl/call-for-papers-failing-on-time-kunstlicht-vol-44-no-1/.

[28] “Tubelight komt geheel onbezoldigd tot stand.” See: https://www.tubelight.nl/over-tubelight/.

[29] Thijs Lijster commented on these “best intentions”: “[People like me who are messing up the market] don’t do so because we’re evil or something, but often precisely because we’re sympathetic to the dire financial circumstances of the magazines and journals. So, we’re willing to accept low or no fees. But obviously this has the negative side effect discussed here.”

[30] See: https://www.mondriaanfonds.nl/en/apply-for-a-grant/grants/curator-researcher/.

[31] The maximum amount depends on the type of the subsidy. See: https://fondsbjp.nl/dutch-fund-for-journalism/.

[32] See: https://www.mondriaanfonds.nl/subsidie-aanvragen/regelingen/open-oproep-kunst-media/.

[33] See footnotes 23 and 24.

[34] A search for “kunstkritiek” on the Boekman Foundation website yields recent discussions on this subject, such as a symposium at the Rijksmuseum and Boekman Magazine’s own issue 106 on art criticism. See: https://www.boekman.nl/?s=kunstkritiek.

[35] From her essay “The Beautiful Risk of Criticality” in the book Spaces of Criticism, co-edited by Thijs Lijster, Suzana Milevska, Pascal Gielen, and Ruth Sonderegger, published in 2015. Details at: https://www.valiz.nl/publicaties/spaces-for-criticism.

[36] See the news report in footnote 3. The journalists are Ruud Rogier (press photographer) and Britt van Uem (journalist).

[37] See: https://www.platformbk.nl/en/graduates-of-art-academies-deserve-more-agency-over-their-future/.

[38] Furthermore, from 2021 on, the Mondriaan Fund has required institutions that receive its funding support to implement Fair Practice Code, which includes fair payment of artists. Read the report on the Experimenteerreglement Kunstenaarshonorarium at: https://bknl.nl/wp/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Evaluatie-Richtlijn-en-Experimenteerreglement-Kunstenaarshonorarium-dd-25-juni-2021_corr.pdf.

[39] Of course, this proposal is accompanied by complexity. For example, which publications/platforms would get such a budget? How would this affect existing commercial activities, if any? Would it also raise fees for authors who do not write for money (e.g. academics and salaried curators)? Could one start a new platform and enforce fair pay this way? For now, my proposal remains the beginning of a possibility and requires further discussion.