Precarious Practices #5: On the vulnerability of an art community that must succeed.

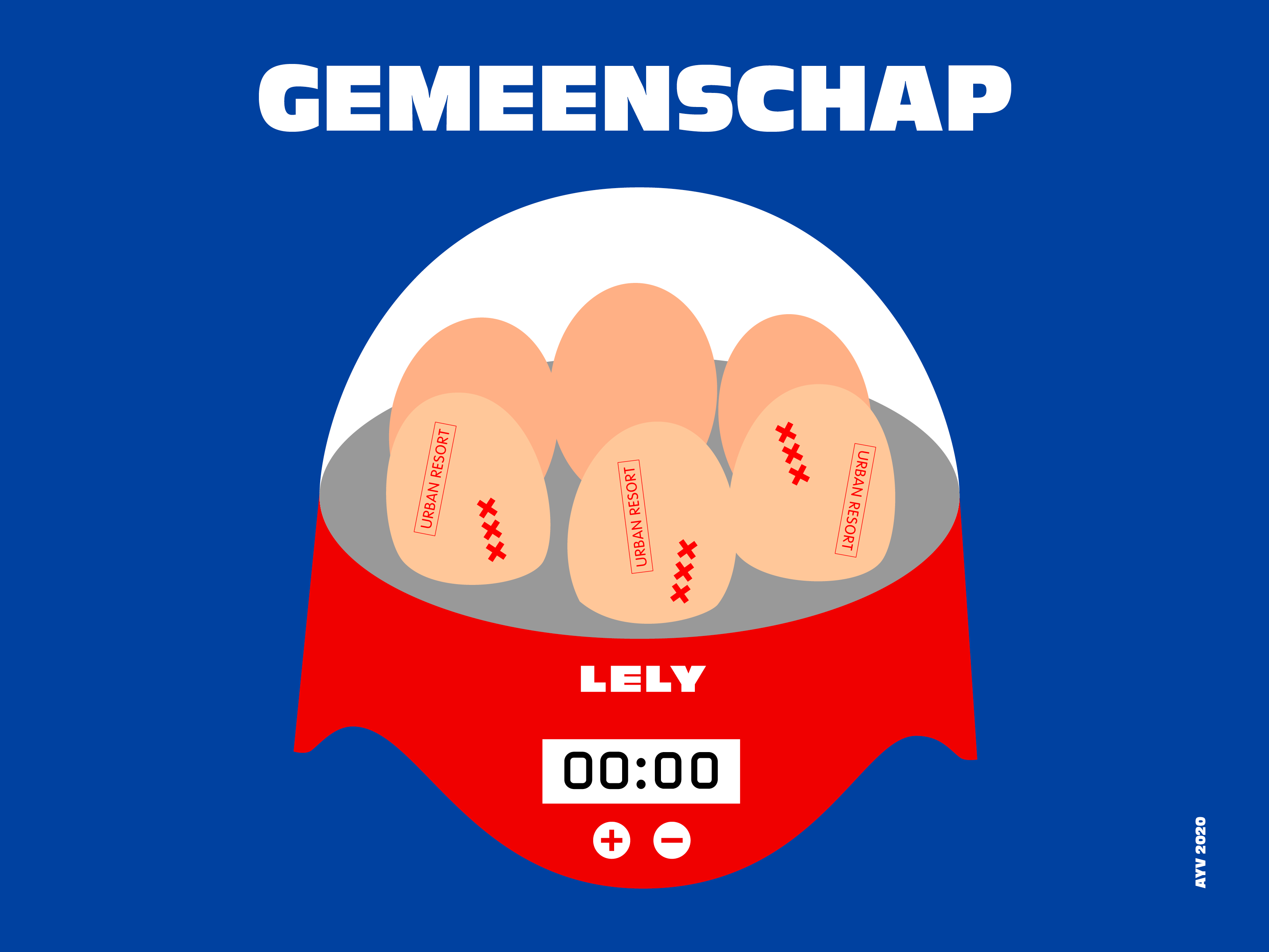

Right before the ‘intelligent lockdown’ was broadcast on national news, as a result of the Covid19 pandemic, I handed in my thesis about the artist community in which I reside. The fact that this announcement took place just after handing in my thesis was not only ironic because that what previously withheld me from having any social contact (completing my thesis) had now been replaced by a mandatory lockdown- but it was also ironic because the coronavirus put a lot of what I had been criticizing in my thesis, in a different perspective. I was arguing that the artist community in ‘Broedplaats Lely’ (for those unfamiliar with the term broedplaats: a broedplaats literally translates into incubator and is a collectively shared building for artists and entrepreneurs in the cultural and creative sector) in Amsterdam was an artificial community and I posed the question if this could rightfully be called a community at all.

Changes that coincide with crises often cause instability. Recently that led to the closing down of many organizations in precarious positions. This was also the case for organizations located in Broedplaats Lely. At the same time, major changes can also uncover opportunities in, what previously seemed, to be an impenetrable system. I had just concluded my research on the artist community in Broedplaats Lely – a study critiquing the false pretenses under which these communities are established and the rigid frameworks in which the artist is expected to maneuver. The consequences of the pandemic, however, underlined the value of a community; displaying how communities operate and why now, more than ever, it is crucial to save space for the formation of sustainable and lasting communities.

Feelings of togetherness are important to us. This was made clear by recent advertisements assuring us that we were all forced into isolation in order to help each other, we were all isolating together. In the supermarkets songs on the radio were interrupted by emotional requests laden with sentimental, cinematic music; requesting us to keep distance and to do so together. Companies have of course been using people’s desire to feel connected as promotional means for years and the interest of community is, currently, being applied more frequently as a reason to establish social projects.

As a person in my late twenties with an income quite below average, I would often stumble upon such community projects throughout my search for housing. In Amsterdam it’s difficult to find affordable housing but there are arrangements where, for example, you can receive rent reduction in exchange for community service. Perhaps this turn to community is a response to the growing individualism of our society or perhaps it is an answer to our disappearing welfare state, nevertheless, the coronavirus crisis made apparent how many people live in isolation and experience loneliness.

Members of a community take care of and support each other, and communities contribute to people feeling like they are a part of something. Still, when the supermarket is using sentimentality to connect me to my fellow consumer (who is hopefully keeping 1,5-meter distance in the narrow shopping aisles) I likewise wonder what the underlying intention is of housing corporations or organizations when they are promoting the establishment of community projects.

Artists being utilized as tools of gentrification has become a well-known phenomenon. To quote Ronald Mauer, member of the Amsterdam city council in 2017, in newspaper Trouw: “First the artists and creatives come; their arrival attracts cafés and other establishments, and this makes the neighborhood attractive for a new kind of inhabitant. That way an entire area receives a boost.”[1] Theorists Jon Coaffee and Stuart Cameron have distinguished current urban regeneration as ‘third wave’ gentrification: in the so-called ‘first wave,’ the artists moved to the periphery in search of larger and affordable studio spaces, in the ‘second wave’ this art and the artist’s surrounding get turned into private commodities and in the ‘third wave’ there is a “more explicit public policy engagement and link to regeneration” taking place with an emphasis on the public consumption of art in order to give specific areas this so-called boost.[2]

As a professional artist I am of course pleased that the local city council acknowledges the importance of art. This allows opportunities for living and working in the city for artists like myself. The problem with the current system is that it offers little flexibility. The artist may live, work and create within frameworks put into place by institutions like the municipality, housing corporations and broedplaats-managers. An example of this problematic policy is Broedplaats Lely, where I live together with over fifty other artists.

In the year 2017, the selected artists moved into the broedplaats, a former school building located in the quickly developing area of Nieuw-West, near the Amsterdam Lelylaan station. Part of the application procedure of the broedplaats-managers Urban Resort, consisted of sending in a portfolio and writing a proposal for a public program that would take place in the large auditorium of the old school building. We received a three-year contract and within this timeframe our artistic plans were expected to unfold. As soon as the construction of the surrounding area would subside the artists could make space for ‘a new kind of inhabitant’; in this case middle- and higher-income residents. Even though we were all selected on the basis of our promising proposals, in actuality, very few would be executed. Every now and then the venue was used but mainly by the arts institutions that were also tenants in the building, such as De Appel Arts Centre and the electro-instrumental studio STEIM. (Recent budget cuts have led STEIM to terminate their lease at Broedplaats Lely and the future of the organization is unclear.) For individual artists the threshold somehow turned out to be too high.

The Amsterdam broedplaats policy was constructed in the year 2000; within the quickly developing city the initiators of the policy noticed that spaces for creative experimentation were rapidly disappearing. This policy came into place to preserve space for the low-earning ‘free spirited’ inhabitants so that they too could hold a space in the gentrifying city of Amsterdam. However, this format received a lot of criticism. The bureaucracy behind the policy made it too complicated for artists to establish their own broedplaats. In response to this, the broedplaats management organization, Urban Resort, was formed. Composed of a group of people with origins in the Amsterdam squatting scene but likewise possessing the required bureaucratic knowledge, they could serve as the link between municipal institutions and the artist. In this way, despite the disappearance of free-spaces, (designated spaces reserved for creative experimentation established through squatting) space for experimentation could still be safeguarded.

Yet the most important element of experimenting is perhaps the possibility of failing and in Broedplaats Lely there is little space to fail. For this city’s standards, the rent per square meter in the building is relatively low, but for a majority of tenants, the rent amounts to over €600, – per room. To give an impression of what most artists earn; the TOZO (a temporary income support system for self-employed entrepreneurs and freelancers, set up as a result of the pandemic) of €1.050, – was quite a major relief in comparison to their standard income. Even though Broedplaats Lely is an example of relatively affordable housing, there is still little space for the artist to make mistakes. In order to cover these bills, multiple side jobs are often needed, and that does not include the costs of financing your own art. We were a selected group of individual artists, put together in a building and deemed a community. But there is no room to care for one another when you are struggling to keep your own head above water.

Surprisingly, the corona crisis changed this. The implemented restrictions did lead to most of us suddenly being unemployed, but this instability created space for solidarity, bringing us closer together. Broedplaats Lely felt like (excuse the perhaps inappropriate comparison in this case) a cruise ship offering a variety of daily activities. We started organizing our own yoga lessons, hosted movie nights and played games together, we suddenly had time to focus on art and try out new ideas, we spent time gardening and even started a compost pile. A fellow tenant stated what we were all feeling: we could temporarily and free of guilt, take time for ourselves and for our art.

As an autonomous artist you are always in search of the next project or assignment and this makes it a challenging and diverse profession. Of course, when there is financial shortage then the search for the next project can be stressful. Being self-employed means that the responsibility always falls on you; you can always do more, work harder, search further. But we could not do a thing about the corona crisis. The TOZO benefit, as mentioned earlier, was a relief for many but not everyone was eligible for this. The tenants got into contact with each other, there was talk of a rent-strike in solidarity with those who were financially affected the most. Our thoughts on the rent strike and how to proceed differed, but for the first time a collective movement was brought into place.

A collective email address was formed in name of the tenants, a letter was put together addressing our landlords and a representative from each wing of the building helped in writing it. The meetings suddenly drew a large attendance, in contrast to the previous meetings over the years that had been hosted by the building’s managers. But I do not want to make it sound better than it is – after a couple of months the community started to crumble. Many of us went back to our side jobs, bills needed to be paid and the attendance of our gatherings started to decline. We were back to being a group of individual artists living amongst each other.

This essay is not about whether or not the proposed rent strike succeeded. For those who are curious, the answer is not really; there was no lasting strike, but the efforts did lead to a payment plan for those affected most. But this text is about what these circumstances have made clear to us. Never before had I felt so connected to my fellow tenants. During the lockdown there were two aspects that led to collective action: we had a common goal and we had time. Still, this equation lacks stability and space which led to our collective withering away just as quickly as it had been formed.

Members of a community stand up for each other, but what signifies a community is that it creates and defines itself. The tenants of Broedplaats Lely were already deemed a community, but ironically this was only actualized once its members stood up against the organization that had labeled them so. A community is not established through a top-down structure determining the frameworks through which the community can maneuver. Communities are formed through trust and in order to gain trust one needs time, space and support. In temporary living situations, like Broedplaats Lely, the inhabitants hardly get a chance to ground themselves. By the time the artists get to know each other and understand how they can be of use to each other and their surroundings, it will be time for them to leave.

We seem to be caught in a vicious circle. The municipality determines which projects are allowed to happen where and for how long, the broedplaats managers receive temporary space based on their promises to establish beautiful artist communities that will help boost the neighborhood, and the artist participates in this contest, putting into words what is expected of them in order to get through the application procedures that will grant them a space in the evermore competitive city of Amsterdam. To create sustainable connections with the city its inhabitants likewise need sustainable living and working opportunities. If the duration of a space, working conditions and participants are predetermined by an institution then that leaves no space for its members to form their own definitions, have agency or autonomy.

Communities are legitimate answers to the growing individualism of our society and preserving space for experimentation is a fantastic way to keep a city creative and diverse. However, a predefined community is an artificial community and from experimenting without failing, you are left with, at most, mediocre art.

[1] “Eerst komen er kunstenaars en dergelijke. Hun komst trekt horeca en andere voorzieningen. En dat maakt een buurt aantrekkelijk voor een nieuw soort bewoner. Zo kan een hele buurt een boost krijgen.” – Ronald Mauer, D66 bestuurder. From: Obbink, Hanne. “Broedplaatsen voor kunstenaars laten Amsterdam bruisen.” Trouw (Amsterdam), June 11, 2017, https://www.trouw.nl/nieuws/broedplaatsen-voor-kunstenaars-laten-amsterdam-bruisen~bed7b427/.

[2] Cameron, Stuart, and Jon Coaffee. “Art, Gentrification and Regeneration: From Artist as Pioneer to Public Arts.” International Journal of Housing Policy 5, no. 1 (2005): 39-5.

The Dutch version of ‘The Artificial Community’ was awarded a basic prize in the 2020 edition of the Prijs voor Jonge Kunstritiek (Prize for Young Art Criticism).

Claire van der Mee was brought up bilingually in Los Angeles and Amsterdam and graduated as a visual artist from the Gerrit Rietveld Academy in 2016. Besides making visual work, she often writes, gives art workshops to children, works in a silk-screen workshop, and spends a lot of time gardening. She completed her master's study, Arts & Society, at the University of Utrecht in the year 2020.