Precarious Practices #4. On what the numbers show us, and the qualitative insights we can derive from that.

Recently, CBS (Statistics Netherlands) published an article with data about culture, sport, and recreation.[1] Although these figures are not new, they do show how vulnerable the labour market is within the cultural and creative sector in the midst of the corona crisis. The proportion of one-person businesses had never been higher than it was when the cultural sector had to shut its doors in mid-March. What do these figures tell us about labour relations in the cultural sector? And why is this topic especially important now?

These questions formed a starting point for a discussion between Claartje Rasterhoff and Bjorn Schrijen with philosopher of art and culture Thijs Lijster on the cultural labour market before and after corona. Just as culture makers’ work practice served as a model for labour organisations in recent decades, they may now play a pioneering role in the development of alternative forms of organisation, such as collective associations and self-organisation.

The numbers

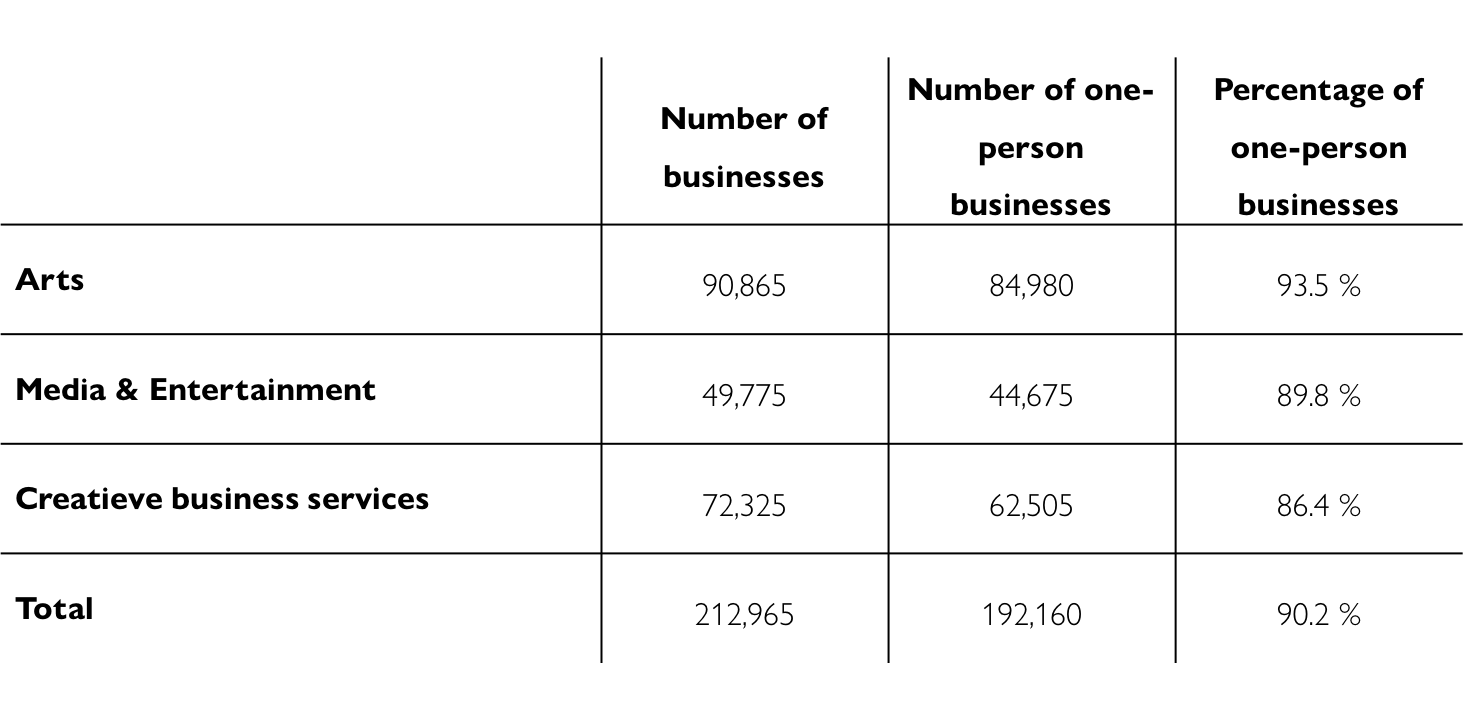

First, the numbers. If we look at the sub-sectors that were included in the ‘art’ category in the Standaard Bedrijfsindeling (Standard Business Classification, SBI) of the CBS, then it appears that in the second quarter of 2020, 88,620 businesses were active within these sectors. 83,520 of these are one-person businesses, amounting to 94.2%.[2] Even if we use a significantly broader definition of the cultural and creative sector like in Table 1, the share of one-person businesses remains very high.[3]

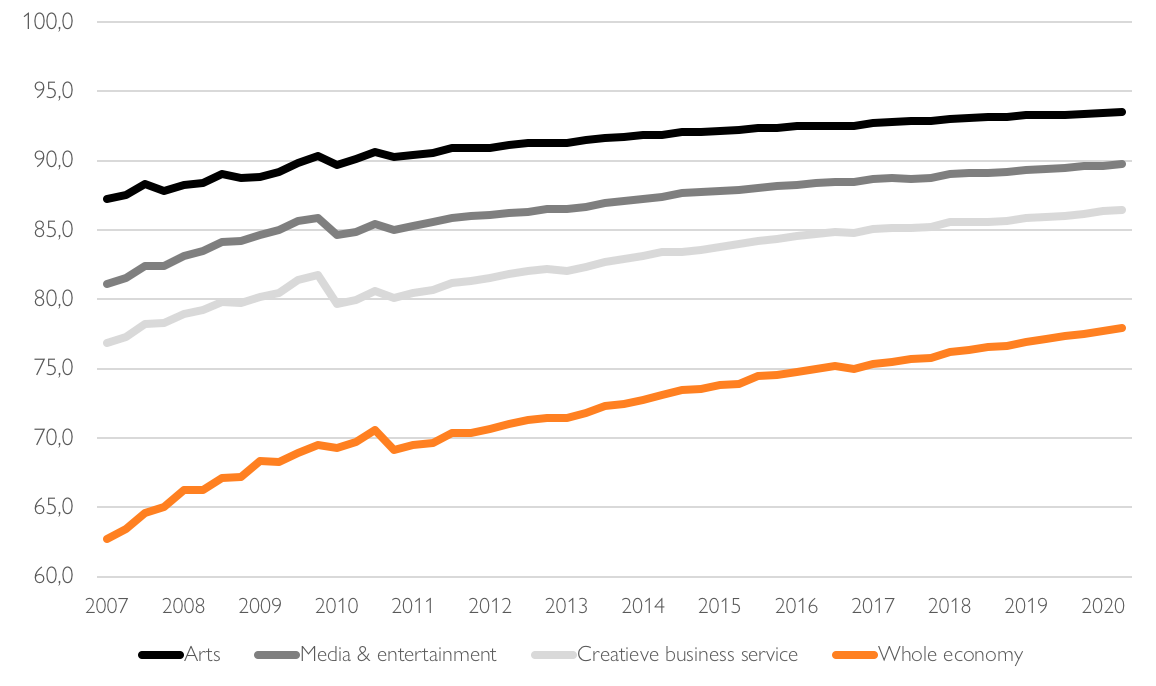

The percentage of one-person businesses in the cultural and creative sector has always been high – and given makers’ individual practices, not surprising – but since the start date of this data series in 2007, the share has undeniably increased further. Moreover, the percentage of one-person businesses in the cultural and creative sector is considerably higher than in the economy as a whole, where at the moment 78% of all businesses are one-person enterprises.[4]

Due to the high number of one-person businesses in the cultural sector, there is also an above-average number of people who earn their income through self-employment. In 2016, there were 124,560 self-employed persons and 146,490 employees in the sector.[5] Based on this and previous data from Statistics Netherlands, it seems to be a safe assumption that in 2020, half of those working in the cultural and creative sector are self-employed. Thus, the share of self-employed persons in the cultural and creative sector is higher than in the economy as a whole, where at the end of 2019, 16.7% of the working labour force (primary) were self-employed.[6]

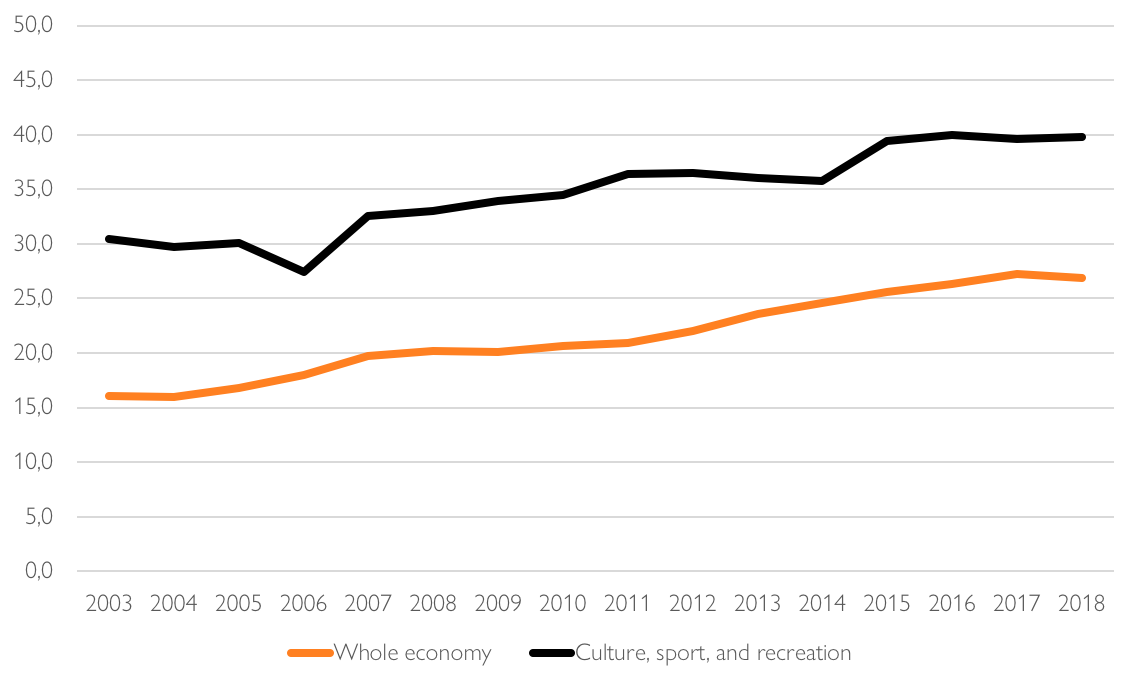

If you present these figures to Thijs Lijster – author of Verenigt u! Arbeid in de 21ste eeuw, (Unite! Labour in the 21st Century, 2019) – he immediately remarks that the self-employed are not necessarily economically vulnerable. It is quite possible to create financial security from independent entrepreneurship, and working independently can in fact also contribute to a feeling of autonomy and control. Also, self-employed workers are not the only group of workers who may be vulnerable in this crisis. Cultural sector employees with a temporary or flexible contract can quickly end up with financial difficulties if employers do not extend their contracts due to profit losses, reduced demand, or uncertainty. At the end of 2018, 26.7% of all employees in the Netherlands had such a flexible employment arrangement. In the culture, sport, and recreation sector, this proportion was 42.6%; after horeca (the hotel, restaurant, and café industry, 62.0%) the highest share of all major categories in the SBI.[7]

When we try to estimate the vulnerability of participants in the cultural labour market, we shouldn’t only look at the labour relations, but also how they interact with social arrangements and other dimensions of job security. Sociologists, economists, and philosophers are increasingly designating work that offers insufficient or no income security as precarious work. The emphasis here lies on how labour associations are organised, who benefits from them and who does not, and how precariousness can help to expose forms of faux-self-employment and (self-)exploitation. Lijster points to the work of economist Guy Standing, who distinguishes different forms of labour security. In his book The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class (2011), Standing also distinguishes between security in the durability of knowledge and skills, and security in autonomy over one’s position and representation in (political) negotiations.[8] If we apply these last two dimensions to creative work, you can, according to Lijster, say that individual creative work also becomes precarious because the sector as a whole is precarious as a result of declining and uncertain public funding.

In addition to the type of labour arrangement and the contract type, let’s also look at wages and social security. On average, wages in the cultural sector are considerably lower than in the economy as a whole. In 2018, the average hourly wages within the SBI code ‘culture, sport, and recreation’ amounted to €20.47, compared to €22.69 in the economy as a whole. If this is extended to monthly and annual wages, a cultural worker earns an average of €729 per month and €11,080 per year less than the average employee in the Netherlands.[9] Only employees in the horeca sector and the ‘rental and other business services’ sector earned less on an annual basis.[10] Self-employed persons within the ‘culture, sport, and recreation’ sector also have a much lower income than colleagues in other sectors: their average personal annual income in 2018 was €12,000 lower than the average annual income of self-employed persons in the economy as a whole. Moreover, financial reserves in the form of wealth among self-employed persons in the ‘culture, sport, and recreation’ sector are the smallest of all economic sectors.[11] It’s hardly surprising then that the call for better wages in the cultural sector has been resounding loudly in recent years, which resulted in the Fair Practice Code that was introduced last year.

The social safety net also doesn’t provide security for everyone. The Zelfstandige Enquête Arbeid (Self-employed Labour Survey, ZEA) conducted among more than 5,500 self-employed entrepreneurs shows that many self-employed persons without employees (zzp’ers), including in the cultural sector, do not have disability insurance or pension provisions. At the beginning of 2019, more than four in ten self-employed persons without employees indicated that they had no disability provisions whatsoever. They do not have insurance for their self-employed work, do not participate in a bread fund, and also cannot fall back on savings, investments, or capital invested in their company or home.

Precarious work

Thus, a large part of the cultural sector consists of zzp’ers and employees with flexible contracts, many of whom have relatively low incomes, small buffers, and few social provisions. It is therefore not surprising that they are experiencing acute financial difficulties now that the demand for their services and products is decreasing due to corona and has in some cases vanished completely. Although some entrepreneurs and zzp’ers are eligible for temporary provisions like TOZO (Tijdelijke overbruggingsregeling zelfstandig ondernemers, Temporary Bridging Measure for Self-employed Professionals) and TOGS (Tegemoetkoming Ondernemers Getroffen Sectoren, Reimbursement for Entrepreneurs in Affected Sectors), many have been left out. For example, recent research into the music industry commissioned by Buma/Stemra and Sena showed that 40% of the more than 2,000 (self-employed) entrepreneurs surveyed have claimed TOZO and about 10% have claimed TOGS. One third of the respondents in the survey indicated that they are not eligible for the temporary provisions.

The CBS numbers confirm the picture of uncertainty and vulnerability that has emerged from recent studies into the consequences of corona for makers in the cultural sector. But perhaps the numbers can offer us even more now that, for example, the Raad voor Cultuur (Council for Culture) is developing scenarios for the future of the cultural sector. They also remind us that the economic vulnerability of the cultural labour market is partly due to the organisation of labour relations. Of course, the individual manner of working, which is often not demand driven, and thus entails a particular degree of uncertainty, is something of an integral part of some creative labour. With the increasing importance of creativity in the development of economic activities in recent decades, the professional practice of artists and other creative makers has served as a model for the many ‘non-standard jobs’ that have replaced the traditional standard full-time position in recent decades, as Lijster describes in Unite!

Connection and solidarity

What should we do now that the consequences of the corona crisis confirm that work in the cultural sector is, to a considerable extent, precarious? Lijster sketches a serious dilemma: how can we create a common destiny and make new connections with each other despite the physical distance? Flocking to the Malieveld does not seem like an option for the time being. He also notes that culture makers sometimes show little solidarity. By offering their work for nothing or little, makers can undermine the collective and unintentionally also contribute to the loyalty calculus of clients and employers.

Nevertheless, Lijster thinks that the cultural sector can play a pioneering role in addressing job insecurity and stimulating solidarity, especially when it comes to connecting with other sectors. Just as culture makers’ professional practice served as a model for labour organisation in recent decades, they may now play a pioneering role in the development of alternative forms of organisation, such as collective associations and self-organisation. In addition, Lijster argues, artists can use their imagination to play an important role in making personal experiences collective, thereby connecting the self-employed and employees in various domains and internationally.

Just after we spoke to Thijs Lijster on the phone, white statues of a supermarket stock clerk, an artist, a cleaner, a rubbish collector, a nurse, a teacher, a police officer, a journalist, our prime minister, and the CEO of KLM appeared on the Malieveld. Each on a pedestal, but one slightly higher than the other. With this campaign, initiators Platform BK and creator Yuri Veerman pose the question: ‘How much money does a hero earn?’ (‘Hoeveel geld verdient een held?’). We may not be able to gather en masse on the Malieveld, but we can depict and question precarious work inside and outside the cultural sector.

This article was originally published by the Boekman Foundation as part of the corona platform for research questions and knowledge sharing in culture (coronaplatform voor onderzoeksvragen en kennisdeling in cultuur), through which the Boekman Foundation contributes to the discussion about the impact and consequences of the corona pandemic on the cultural sector. Read more from and about the Boekman Foundation here.

We thank the Boekman Foundation, Claartje Rasterhoff, Bjorn Schrijen, and Thijs Lijster for their generous permission to republish this text.

This article was translated from Dutch to English by Felix van de Vorst and Hannah Vernier.

References

[1] CBS, ‘Feiten en cijfers over de cultuur, sport en recreatie’ (‘Facts and figures on culture, sport, and recreation’), CBS, 24 April 2020, https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/achtergrond/2020/17/feiten-en-cijfers-over-de-cultuur-sport-en-recreatie.

[2] CBS, ‘Bedrijven; bedrijfstak’ (‘Businesses: Industry’) (narrow cultural and creative sector selection), CBS, 15 April 2020, www.opendata.cbs.nl. All the figures on businesses in 2019 and 2020 mentioned in this article have a (further) provisional status in the source data. That is also true of the cited number of self-employed persons in 2016.

[3] CBS, ‘Bedrijven; bedrijfstak’ (‘Businesses: Industry’) (broad cultural and creative sector selection), CBS, 15 April 2020, www.opendata.cbs.nl. This classification of the cultural sector is in line with the classification that the CBS made earlier for Cultuur in Beeld (Culture in the Picture). For an overview of the sub-sectors that fall under this classification, see CBS, Cultuur in beeld 2018 (Culture in the Picture 2018) (The Hague/Heerlen: Centraal Bureau voor de statistiek [Statistics Netherlands], 2018).

[4] CBS, ‘Bedrijven; bedrijfstak’ (‘Businesses: Industry’) (whole economy), CBS, 15 April 2020, www.opendata.cbs.nl.

[5] CBS, Cultuur in beeld 2018, (Culture in the Picture 2018).

[6] CBS, ‘Arbeidsdeelname; kerncijfers’ (‘Labour participation: Key numbers’), CBS, 13 February 2020, www.opendata.cbs.nl.

[7] CBS, ‘Werkzame beroepsbevolking; bedrijf’, (‘Working labour force: Business’), CBS, 29 November 2019, www.opendata.cbs.nl.

[8] Guy Standing, The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class (London: Bloomsbury, 2010), 10.

[9] The monthly amount includes overtime, and the yearly amount includes bonuses.

[10] CBS, ‘Employment Opportunity: Jobs, wages, working hours’, SBI2008: Key figures’ (‘Werkgelegenheid; banen, lonen, arbeidsduur, SBI2008; kerncijfers’), CBS, 30 September 2019, www.opendata.cbs.nl.

[11] CBS, ‘Self-employed Persons: Incomes, wealth, industry’ (‘Zelfstandigen; inkomen, vermogen, bedrijfstak’), CBS, 22 november 2019, www.opendata.cbs.nl.

Thijs Lijster is assistant professor of philosophy of art and culture at the University of Groningen and is also a postdoctoral researcher affiliated with the Culture Commons Quest Office of the University of Antwerp. In 2009 he won the Vrij Nederland essay prize, in 2010 the Prijs voor de Jonge Kunstkritiek (Prize for Young Art Criticism), and in 2015 the Boekman Dissertatieprijs (Boekman Dissertation Prize). 'Kijken, proeven, denken. Essays over kunst, kritiek en filosofie' (Looking, Tasting, Thinking: Essays on art criticism and philosophy) and the book 'Verenigt U! Arbeid in de 21ste eeuw' (Unite! Labour in the 21st century) in the series Nieuw licht (New Light) appeared in 2019.